BEING BROWN REALIA PAGE

This teaching website adds functionality and builds upon topics and themes developed in Being Brown. The website contains two sections. The first is the "figures" section and it complements material discussed in the book by providing added commentary, visual prompts, and ancillary linked material for further reading and study. The second is the "realia" section and it contains material that is intended to enhance class discussions, spark curiosity and promote further research. The materials, commentary, and images curated below are intended for educational purposes. (All required permissions have been obtained and sources are listed in parentheses as linked.)

FIGURES

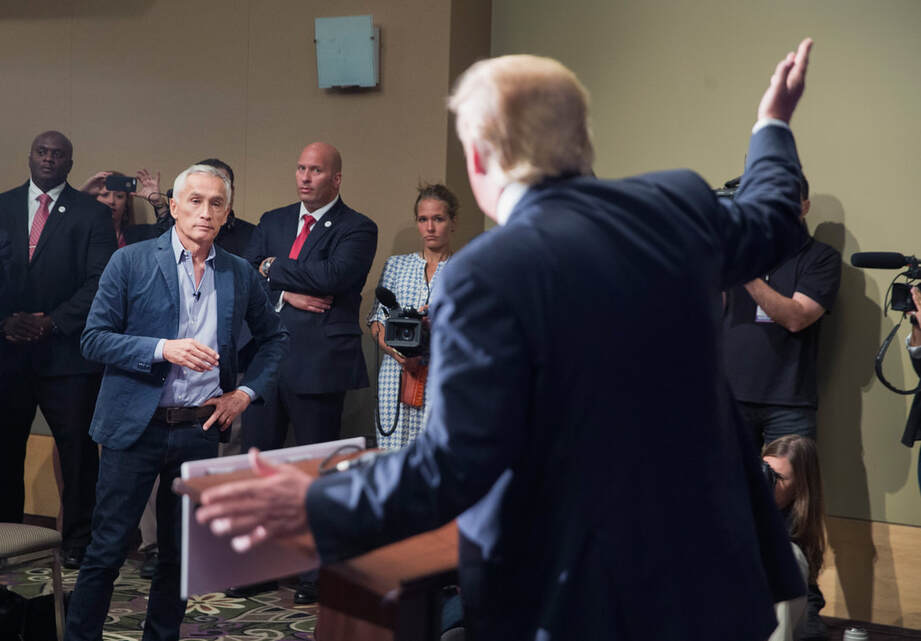

Author Website, 1. Univision anchor and reporter Jorge Ramos before being “deported” from a Trump press briefing on August 28, 2015. During the briefing, Trump screamed “Go back to Univision!” as Ramos was escorted out of the room. The dogwhistle rejoinder was another way of exclaiming the racist and white-nationalist invective, “Go back to Mexico!” Trump later told reporters that Ramos was “just the first of many Mexicans” he would “kick out” of the country if elected. (Photo credit by permission and source as linked: Scott Olson/Getty Images)

Author Website, 2. Crews work on a border wall prototype near the border with Tijuana, Mexico, in San Diego. While several companies competed for the border wall contract only two received the commission for building the wall. The first, Elta North America, is a U.S. subsidiary of Elta Corporation of Israel, and the largest builder of prisons in the U.S. The second company, KWR Construction Incorporated of Arizona, is described as a "small, Hispanic-owned company," and one of the Department of Homeland Security, Defense, and Interior's largest customers. (Photo credit by permission and source as linked: Gregory Bull/AP Photo)

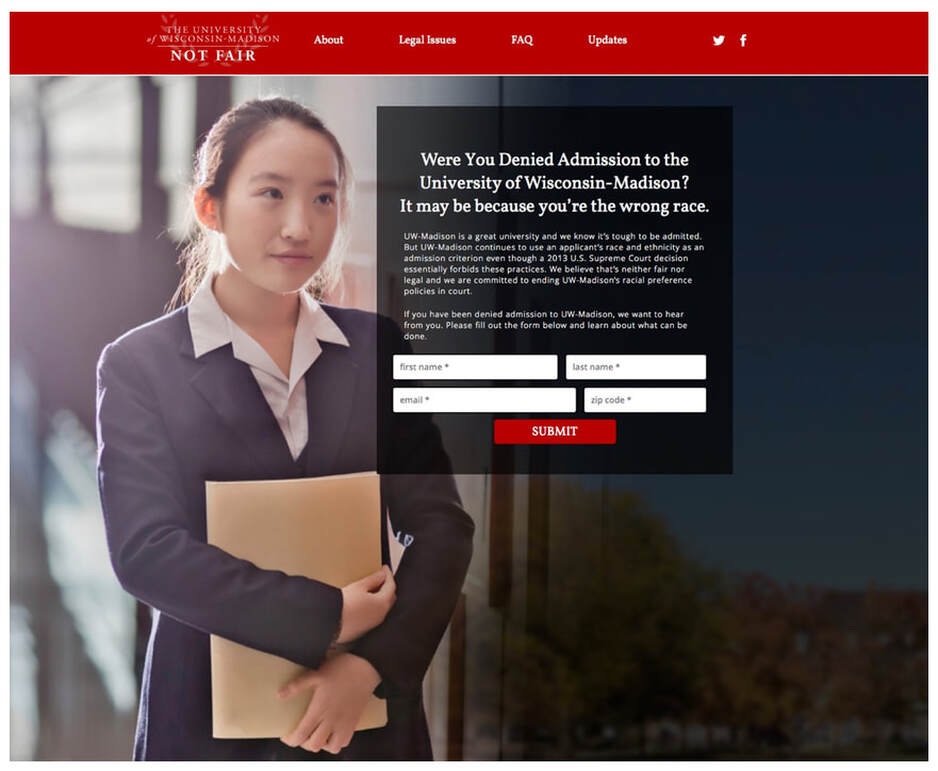

Author Website, 3. Seeking to pit underrepresented minorities against each other, the imprecisely named Project on Fair Representation (POFR) began filing lawsuits on behalf of students rejected from admission to major universities in order to ostensibly eliminate all considerations related to “race” and “ethnicity” in university admissions. POFR is funded by Project Liberty, Inc., a tax-exempt legal "charity" run by Edward Blum. Media Matters for America reported that Blum's work has been funded by financial silent partners, or "Dark Money ATMs," through far right foundations and organizations. Blum was the public face behind the two Fisher vs. University of Texas-Austin lawsuits that reached the Supreme Court in 2013 and 2016. The image above initially appeared on POFR's landing website in order to recruit students denied admission to the University of Wisconsin for the purpose filing suit against the university. This initial recruiting site and campaign served as the template for POFR's other websites seeking to recruit students rejected from admission at other universities. The POFR website lists their active lawsuits against what remains of affirmative action, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. POFR's pending affirmative action cases include lawsuits against Harvard University and the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. (Source image as linked from POFR recruitment page and POFR Cases)

Author Website, 4. "Members of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps wearing gas masks and testing them for proper adjustment during a drill, First Women's Army Auxiliary Corps Training Center (1943)." (Photo credit courtesy NYPL and source as linked: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, New York Public Library Digital Collections)

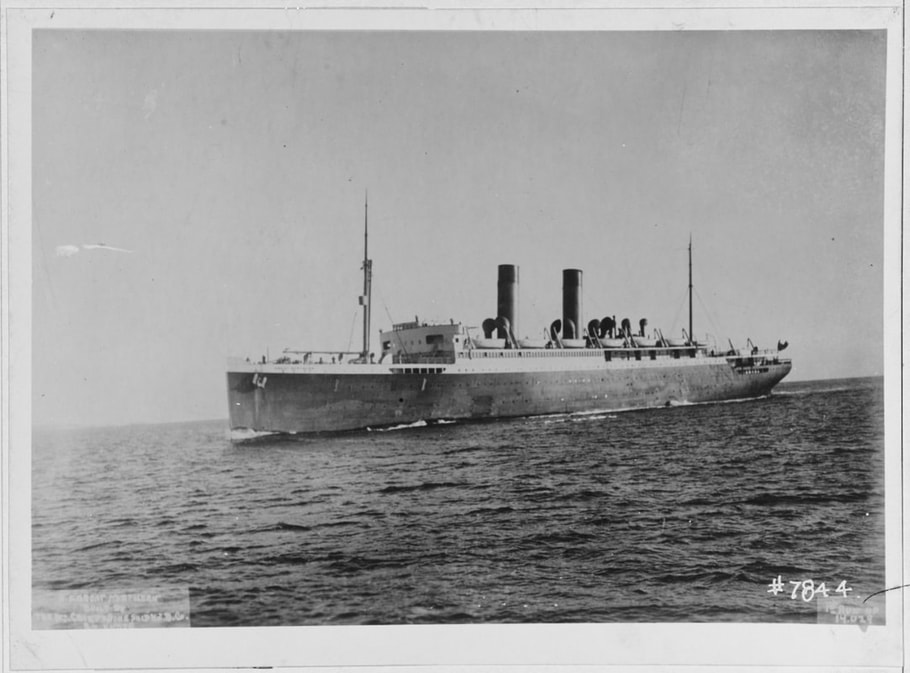

Author Website, 5. The Naval History and Heritage Command Collection of photographs caption reads: "USS Great Northern held the record for speedy 'Turn-Arounds' during World War I." (Photo credit as linked: NH 63217 courtesy of the Naval History and Heritage Command).

The Naval History and Heritage Command Library's history of the ship reads:

"In January 1918 the ship carried passengers from the Pacific to the Atlantic Coasts and in March began her first wartime trans-Atlantic voyage. From then until November 1918, when the Armistice brought the fighting to an end, Great Northern took more than 28,000 passengers to the European war zone. This work was interrupted on 3 October, when a collision with the British ship Brinkburn left seven of her Army passengers dead and about fifteen injured. After the Armistice, Great Northern returned World War I veterans from France. In eight round-trip voyages for this purpose, she brought home nearly 23,000 passengers. In mid-August 1919, USS Great Northern was decommissioned and transferred to the U.S. Army Transportation Service. Subsequently operating as the Army transport Great Northern, Navy fleet flagship Columbia, commercial passenger ship H.F. Alexander and Army Transport George S. Simonds, she was sold for scrapping in Februay 1948."

(Source text quoted as linked: Navel Historical Center Library of Selected Images)

The Naval History and Heritage Command Library's history of the ship reads:

"In January 1918 the ship carried passengers from the Pacific to the Atlantic Coasts and in March began her first wartime trans-Atlantic voyage. From then until November 1918, when the Armistice brought the fighting to an end, Great Northern took more than 28,000 passengers to the European war zone. This work was interrupted on 3 October, when a collision with the British ship Brinkburn left seven of her Army passengers dead and about fifteen injured. After the Armistice, Great Northern returned World War I veterans from France. In eight round-trip voyages for this purpose, she brought home nearly 23,000 passengers. In mid-August 1919, USS Great Northern was decommissioned and transferred to the U.S. Army Transportation Service. Subsequently operating as the Army transport Great Northern, Navy fleet flagship Columbia, commercial passenger ship H.F. Alexander and Army Transport George S. Simonds, she was sold for scrapping in Februay 1948."

(Source text quoted as linked: Navel Historical Center Library of Selected Images)

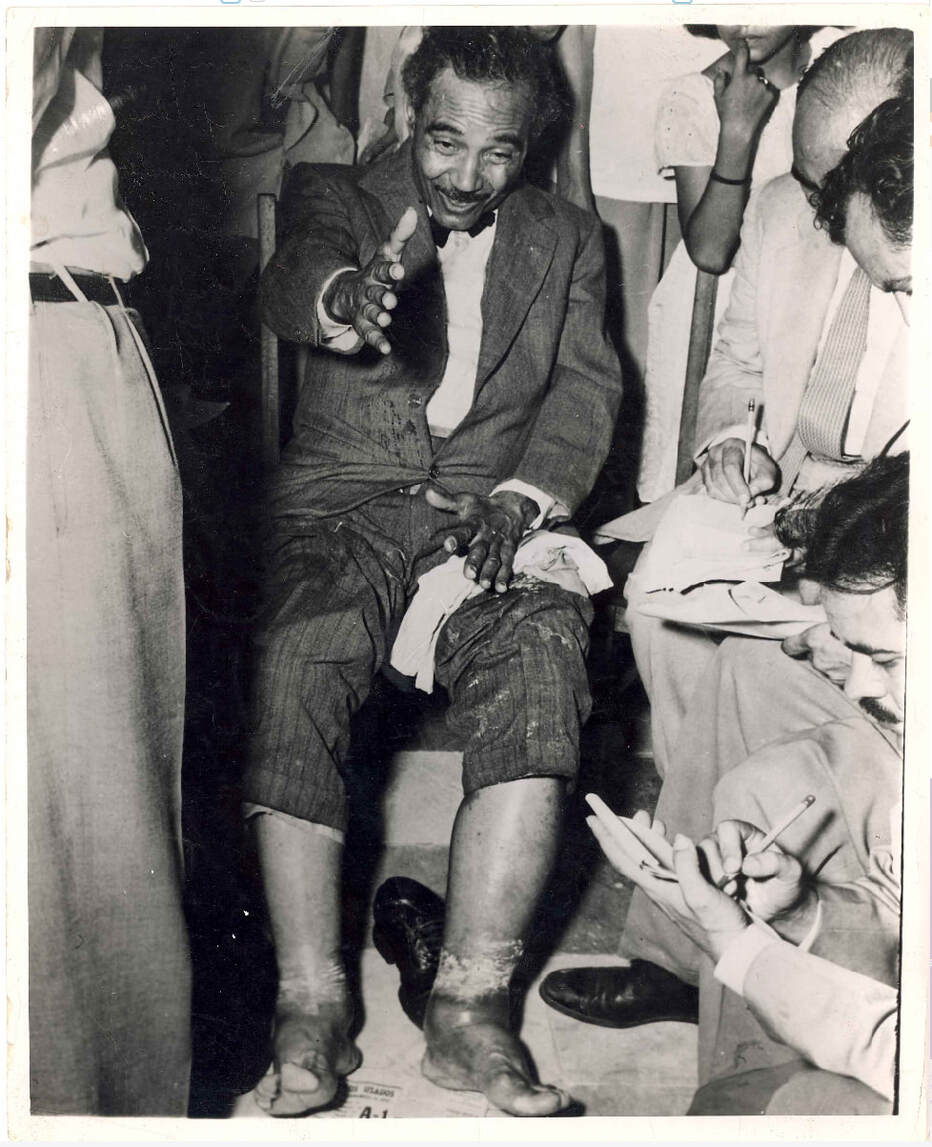

Author Website, 6. Various images of Pedro Albizu Campos showing what appears to be radiation exposure clandestinely circulated on the island. Albizu Campos accused Rhoads of committing crimes against him and other Puerto Rican political prisoners, including radiological and biological experimentation. The images made their way to news outlets in Cuba, Mexico, and the Americas. The image above is part of the important trove of materials, photographs, and artifacts from the Ruth M. Reynolds collection housed at the Archives of the Puerto Rican Diaspora, Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, Hunter College, CUNY. (Photo credit courtesy and source as linked: Ruth M. Reynolds Papers, 1915-1989, "Albizu Campos Sitting In Chair With Swollen Legs," Center for Puerto Rican Studies Library & Archives, Hunter College, CUNY)

Author Website, 7. Dolores "Lolita" Lebrón Sotomayor was arrested along with Rafael Cancel Miranda, Irving Flores Rodríguez, and Andrés Figueroa Cordero shortly after the March 1, 1954 attack in protest of the U.S. occupation of Puerto Rico. The Capital Police staged a series of photos of the arrest. In the image above, the U.S. Capital Building both framed the arrest and allegorized the capture of the Puerto Rican Nationalists under the Capital dome's main entrance. In the image, the Puerto Rican Nationalists were, like the island itself, under U.S. domination. At the request of photographers both Cancel Miranda and Figueroa Cordero had to be literally hoisted by Capital police in order to make them appear to be taller and more imposing than Lolita. The image of the arrest that ultimately made headlines in various U.S. newspapers cropped the photograph so as to hide how both men were floating above the wet asphalt. (Photo credit by permission: AP Photo)

REALIA

Map of Mexican Territories Ceded to the U.S. After the U.S. - Mexico War (1846-48)

(Source image above credit as linked: Wikimedia Commons)

What is "Latino identity" and how is it codified by the state?

It depends who you ask but ethnic studies scholars, along with interpretive humanities and social science scholars, are clear about the term's use value in social science and cultural studies research. Scholars define Latinos as people of Latin American ancestry living in the United States. In order to more fully answer the question let's consider historical context and source material for this definition.

The Spanish and Portuguese settlements and eventual colonization of the Americas from 1492 onward bequeathed what we today call “Latino” cultural identity in the United States. For example, the map above marks Mexican territories (dark grey) prior to the U.S.-Mexico War of 1846-48. The language, customs, cultures, and traditions brought about by the Spanish colonization of North America remained and expanded after Mexican independence from Spain in 1821. Those cultural traditions continue to be part of the United States’ cultural and historical legacy today. That history, though not part of the nation’s official founding narrative, is significant to our country’s past, its present, and — given the Latino demographic reality — its inevitable future.

We should keep in mind, for example, that after the United States-Mexico War (1846-48), the U.S. annexed over half of Mexico’s northern territories including modern-day Arizona, California, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Colorado, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Wyoming as well as Mexico’s claim to Texas which had been under U.S. occupation since 1836 (the Gadsen Purchase of 1853 further extended Arizona and New Mexico’s territorial line into the Mexican Republic). Still, the annexation of Mexican territories tells only part of the story. With the incorporation of former Spanish dominions such as modern-day Florida, and much of the states in the Gulf of Mexico region, we are left with an historical and cultural lacunae that yet has to be fully accounted for.

In the book, I consider the Supreme Court case Hernández v. Texas (1954) to be of tantamount importance because it extended 14th Amendment protections to peoples of "Latin American" ancestry in the United States. Beyond Hernández v. Texas, the only other definition of either "Hispanic" or "Latino" that established a relationship to the state came from a 1976 law passed by Congress (Public Law 94-311, 94th Congress). The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) developed the definition in 1977 for what today we call "Latinos" so that schools, public health facilities and related government entities could keep track of how many Latinos they served. The law mandated the analysis and collection of data for "Americans of Spanish origin or descent [...]" and described this group as “Americans who identify themselves as being of Spanish-speaking background and trace their origin or descent from Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Central and South America, and other Spanish-speaking countries.” The law was also clear about the need to establish how this definition, understood as a relationship to the state, would address and redress why "a large number of Americans of Spanish origin or descent suffer from racial, social, economic, and political discrimination and are denied the basic opportunities they deserve as American citizens and which would enable them to begin to lift themselves out of the poverty they now endure [...]."

It is of consequence that the definition emerged well after the Hernández v. Texas Supreme Court case codified Latinos as people of "Latin American ancestry in the United States" which was the result of the most important Mexican American civil rights organization's very name: League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC). LULAC had strategically used "Latin American" in an effort to establish lines of ancestry to the Iberian peninsula along with the structural affinity with whiteness that defined its emergence as the most successful Mexican American organization of the post-WWII period.

(For a discussion of the term Hispanic and its valence see the Pew's FactTank News in Numbers, Mark Hugo López, et al., "Who is Hispanic," November 11, 2019).

What is "Latino identity" and how is it codified by the state?

It depends who you ask but ethnic studies scholars, along with interpretive humanities and social science scholars, are clear about the term's use value in social science and cultural studies research. Scholars define Latinos as people of Latin American ancestry living in the United States. In order to more fully answer the question let's consider historical context and source material for this definition.

The Spanish and Portuguese settlements and eventual colonization of the Americas from 1492 onward bequeathed what we today call “Latino” cultural identity in the United States. For example, the map above marks Mexican territories (dark grey) prior to the U.S.-Mexico War of 1846-48. The language, customs, cultures, and traditions brought about by the Spanish colonization of North America remained and expanded after Mexican independence from Spain in 1821. Those cultural traditions continue to be part of the United States’ cultural and historical legacy today. That history, though not part of the nation’s official founding narrative, is significant to our country’s past, its present, and — given the Latino demographic reality — its inevitable future.

We should keep in mind, for example, that after the United States-Mexico War (1846-48), the U.S. annexed over half of Mexico’s northern territories including modern-day Arizona, California, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Colorado, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Wyoming as well as Mexico’s claim to Texas which had been under U.S. occupation since 1836 (the Gadsen Purchase of 1853 further extended Arizona and New Mexico’s territorial line into the Mexican Republic). Still, the annexation of Mexican territories tells only part of the story. With the incorporation of former Spanish dominions such as modern-day Florida, and much of the states in the Gulf of Mexico region, we are left with an historical and cultural lacunae that yet has to be fully accounted for.

In the book, I consider the Supreme Court case Hernández v. Texas (1954) to be of tantamount importance because it extended 14th Amendment protections to peoples of "Latin American" ancestry in the United States. Beyond Hernández v. Texas, the only other definition of either "Hispanic" or "Latino" that established a relationship to the state came from a 1976 law passed by Congress (Public Law 94-311, 94th Congress). The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) developed the definition in 1977 for what today we call "Latinos" so that schools, public health facilities and related government entities could keep track of how many Latinos they served. The law mandated the analysis and collection of data for "Americans of Spanish origin or descent [...]" and described this group as “Americans who identify themselves as being of Spanish-speaking background and trace their origin or descent from Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Central and South America, and other Spanish-speaking countries.” The law was also clear about the need to establish how this definition, understood as a relationship to the state, would address and redress why "a large number of Americans of Spanish origin or descent suffer from racial, social, economic, and political discrimination and are denied the basic opportunities they deserve as American citizens and which would enable them to begin to lift themselves out of the poverty they now endure [...]."

It is of consequence that the definition emerged well after the Hernández v. Texas Supreme Court case codified Latinos as people of "Latin American ancestry in the United States" which was the result of the most important Mexican American civil rights organization's very name: League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC). LULAC had strategically used "Latin American" in an effort to establish lines of ancestry to the Iberian peninsula along with the structural affinity with whiteness that defined its emergence as the most successful Mexican American organization of the post-WWII period.

(For a discussion of the term Hispanic and its valence see the Pew's FactTank News in Numbers, Mark Hugo López, et al., "Who is Hispanic," November 11, 2019).

Being Brown Soundscapes

Being Brown Audiotopias

This section curates and discusses formative audiotopias from Sonia Sotomayor's life story. For Josh Kun, "audiotopias" refer to the experience of being transported to different worlds through soundscapes and sonic registers associated with the places, people, memories, and feelings perceived by listeners (Audiotopia: Music, Race and America, 2005). The audiotopias archived in this virtual playlist are either referenced in Sotomayor's memoir My Beloved World (2013) or were on the top of the charts during the signal years I trace from her life's story in Being Brown.

The soundscapes I curate here also attempt to tell an aural history of an era under erasure by imagining how the music and the sounds that surrounded Sonia Sotomayor's formative years also tell a story about being Brown in America. This is important as the sounds as well as the stories I tell about them also represent an attempt to archive what will likely soon be erased with time as analog cedes to digital, and digital cedes to new recordation technologies, and the attendant forms of cultural remembering and historical forgetting these new technologies bring.

The soundscapes below are archived in, and belong to, the linked source pages. Much like our own memories and the mnemonic devices we use to keep them close to us like, say, photographs, the links below will invariably change, disappear, and go missing over time. Despite the inevitability of loss, searching the terms, people, and places associated with the audiotopias listed below will lead to new aural circuits for memory-making, cultural remembrance, and sonic histories yet to be written. And it is in that sense that audiotopias help to enrich the expansiveness of being alive before we too become memories.

Prelude to Being Brown in "America"

Soundscape 1. Ana María Martínez, "María la O" (2018 performance)

Puerto Rican soprano Ana María Martínez (1971 - ) interprets Cuban/Cuban-American composer Ernesto Lecuona y Casado's zarzuela at the San Antonio Symphony Concert Hall in 2018.

Being Brown is informed by my deep commitment to understanding how identity informs knowledge production, dissemination, and ethnic remembrance. One of the book's central concerns is understanding how being Brown has been marked by histories of racism, to be certain, but also about resistance to the very forms of exclusion and loss that racism enacts on bodies, minds and our collective memory. Put another way, the Black Atlantic is central to understanding how being Brown has created aesthetic forms of redress, rememory and survival.

Ernesto Lecuona y Casado (1896-1963) represents an emblematic case in point to the history of ethnic remembrance and survival. Lecuana introduced Afro-Cuban and Cuban rhythms and instruments to the largely static repertoire of classical music between the two World Wars. His zarzuela, "María la O," premiered in Havana, Cuba, on March 1, 1930, at the Teatro Payret. In "María la O" Lecuona attempted to translate and convey writer Cuban Cirilio Villaverde's novel Cecilia Valdés o la Loma del Ángel (1882 [Cecilia Valdés or Ángel Hill]) as a story of racialized sexual violence through sound and timbre so that hearts could understand what eyes refused to see.

Cuban racism was so normalized into national complacency that, for Lecuona, only sonic registers could counter what historical blindness had obscured. Lecuona, whose work requires the attention of performance studies and music history scholars, was one of the first composers to understand the value of transcribing cultural and historical memory vis-à-vis sound. It is in this sense that he provides the framing musical prelude to Being Brown.

The novel itself attempted to fracture Spanish colonial racism through the story of a white privileged creole, Leandro de Gamboa, and his beloved, Cecilia Valdés, who, unbeknownst to him, is his half sister. Cecilia, who is Black but passes for white, is Leandro's daughter conceived through rape. Failed love, illegitimate governance, and ill-conceived nation building were the results of Spanish colonialism's legacy for both Villaverde and Lecuona.

The colonial subservience to whiteness, as the structuring principle for love and nation, were so stunning to Lecuona that he felt that only locally inflected historical harmonies could repair the historical discord. "Hear me," implores the zarzuela "María la O," or be doomed to failed romance and perpetual bondage. In the name of the zarzuela itself, "María la O[tra]," Maria the O[ther], Lecuona lays bare the Caribbean as the resting place for the Atlantic slave trade's original sin: slavery.

Can you hear Lecuona's historical invocations in Ana María Martínez's brilliant interpretation of "María la O"?

Soundscape 2. Fernando Varela, "En mi viejo San Juan" and "Preciosa" (2017 performance)

Introduction. On Being Brown in the Democratic Commons

Soundscape 3. The Ring, "Savage Lover" (1979 and 1980)

By the time Sonia Sotomayor graduated from Yale Law and joined the Manhattan District Attorney's office in 1979 NYC was experiencing an epic crime wave. The infamous Studio 54 was spinning some of the era's most iconic underground synthesizer hits of the year and "Savage Lover" by The Ring coincided with what became known as the "Tarzan" murders and robberies in NYC that Sotomayor helped to solve as prosecutor. During her years working as assistant district attorney and trial lawyer she prosecuted offenders for robbery, assault, murder, child pornography, and police brutality.

Soundscape 4. Cerrone, "Supernature" (1977)

The French composer and record producer Ceronne had two hits that enveloped NYC record stores and soundscapes in 1979. If Sotomayor ventured into West Village, the ambient soundscape would no doubt have included Cerrone's "Supernature" which had already hit big in England as early as 1977, but settled stateside in late 1978. Along with Ceronne's "Love in C Minor" (1976), both were a fixture of downtown NYC life everywhere you went. While it is hard to imagine from our vantage point, in the absence of privatized soundscapes first introduced by SONY with the Walkman in 1979, someone else's musical tastes always wound up in your sensorium if they possessed the bass and the speaker strength to pump out the sound.

Soundscape 5. ESG, "Moody" (1981)

Like Sonia Sotomayor, the group ESG (short for Emerald, Sapphire and Gold) came of age in the South Bronx. Sisters Renne, Valerie, and Marie Scroggins created a Brown alternative to the music of the era through sheer will because they lacked the resources to buy traditional musical instruments. Instead they used borrowed synthesizers, bass and sheer talent to forge Latinx audiotopias. They're "Moody" is a syntho-disco alternative to the overproduced disco music of the day and was a fixture at the Paradise Garage, itself an epic Black and Brown queer house-music space in NYC that was demolished in 2018. It was in "Paradise," as we called it then, that as an under-age kid with a fake ID I first heard ESG. ESG was "intersectional" before we knew what the term was. They crossed genres as diverse as hip-hop, new-wave, disco, and punk. In the process, they united a truly diverse following that included homies, punksters, audacious divas, and closeted Brown queer boys like me from the NYC suburbs. Dancing to "Moody" felt as close to paradise as I could have imagined it then when ESG's pulsing bass beats reverberated through my body with what felt like freedom. We should never underestimate our petit freedoms. No matter how small, these petit freedoms allow us to inhabit imaginary elsewhere that taste like liberation. And it is in that yearning that we find the will, against escape but toward freedom, to break free from our real or imagined dispossession.

Soundscape 5. John "Jellybean" Benítez, remix of Babe Ruth's "The Mexican" (1984)

During Ronald Reagan's two-term presidency (1981-1989) public education subsidies were slashed and the neoliberal order enshrined austerity for everyone but the wealthiest as corporate taxation exemptions rose in measure with deregulation. The emergence of the "one-per-center" billionaires ballooned as waged labor stagnated under a minimum wage of $3.35 that was supported by the president.

Puerto Rican John "Jellybean" Benítez's remix of "The Mexican" reinterpreted Latinx and Black resistance to stagnant labor, and rising higher educational inequities just as the 1984 reelection campaign for Reagan kicked into high gear. John Wayne, Reagan's favorite movie-star and alter-ego, had stared in the film western The Almo (1960) which distorted the history of U.S. and Texan occupation of Mexico prior to the U.S. Mexico War of 1846-48.

The remix became a house and clubhouse anthem of resistance for urban youth who were introduced to a sonic hero, Chico Fernández, who refused U.S. imperial expansion. The remix of "The Mexican" was a circuit venue hit while Benítez was a DJ at NYC's Funhouse, the Roseland Ballroom, Studio 54 and popularized on NYC dance radio station WKTU which reached into Long Island and southern Connecticut. "The Mexican" was also a staple that year at NYC clubs and Fire Island, NY, where Sonia Sotomayor vacationed as told in her memoir, My Beloved World (2013, Chapter 24, pgs. 226-27).

Link to complete list of soundscapes: Soundscapes 6-21

This section curates and discusses formative audiotopias from Sonia Sotomayor's life story. For Josh Kun, "audiotopias" refer to the experience of being transported to different worlds through soundscapes and sonic registers associated with the places, people, memories, and feelings perceived by listeners (Audiotopia: Music, Race and America, 2005). The audiotopias archived in this virtual playlist are either referenced in Sotomayor's memoir My Beloved World (2013) or were on the top of the charts during the signal years I trace from her life's story in Being Brown.

The soundscapes I curate here also attempt to tell an aural history of an era under erasure by imagining how the music and the sounds that surrounded Sonia Sotomayor's formative years also tell a story about being Brown in America. This is important as the sounds as well as the stories I tell about them also represent an attempt to archive what will likely soon be erased with time as analog cedes to digital, and digital cedes to new recordation technologies, and the attendant forms of cultural remembering and historical forgetting these new technologies bring.

The soundscapes below are archived in, and belong to, the linked source pages. Much like our own memories and the mnemonic devices we use to keep them close to us like, say, photographs, the links below will invariably change, disappear, and go missing over time. Despite the inevitability of loss, searching the terms, people, and places associated with the audiotopias listed below will lead to new aural circuits for memory-making, cultural remembrance, and sonic histories yet to be written. And it is in that sense that audiotopias help to enrich the expansiveness of being alive before we too become memories.

Prelude to Being Brown in "America"

Soundscape 1. Ana María Martínez, "María la O" (2018 performance)

Puerto Rican soprano Ana María Martínez (1971 - ) interprets Cuban/Cuban-American composer Ernesto Lecuona y Casado's zarzuela at the San Antonio Symphony Concert Hall in 2018.

Being Brown is informed by my deep commitment to understanding how identity informs knowledge production, dissemination, and ethnic remembrance. One of the book's central concerns is understanding how being Brown has been marked by histories of racism, to be certain, but also about resistance to the very forms of exclusion and loss that racism enacts on bodies, minds and our collective memory. Put another way, the Black Atlantic is central to understanding how being Brown has created aesthetic forms of redress, rememory and survival.

Ernesto Lecuona y Casado (1896-1963) represents an emblematic case in point to the history of ethnic remembrance and survival. Lecuana introduced Afro-Cuban and Cuban rhythms and instruments to the largely static repertoire of classical music between the two World Wars. His zarzuela, "María la O," premiered in Havana, Cuba, on March 1, 1930, at the Teatro Payret. In "María la O" Lecuona attempted to translate and convey writer Cuban Cirilio Villaverde's novel Cecilia Valdés o la Loma del Ángel (1882 [Cecilia Valdés or Ángel Hill]) as a story of racialized sexual violence through sound and timbre so that hearts could understand what eyes refused to see.

Cuban racism was so normalized into national complacency that, for Lecuona, only sonic registers could counter what historical blindness had obscured. Lecuona, whose work requires the attention of performance studies and music history scholars, was one of the first composers to understand the value of transcribing cultural and historical memory vis-à-vis sound. It is in this sense that he provides the framing musical prelude to Being Brown.

The novel itself attempted to fracture Spanish colonial racism through the story of a white privileged creole, Leandro de Gamboa, and his beloved, Cecilia Valdés, who, unbeknownst to him, is his half sister. Cecilia, who is Black but passes for white, is Leandro's daughter conceived through rape. Failed love, illegitimate governance, and ill-conceived nation building were the results of Spanish colonialism's legacy for both Villaverde and Lecuona.

The colonial subservience to whiteness, as the structuring principle for love and nation, were so stunning to Lecuona that he felt that only locally inflected historical harmonies could repair the historical discord. "Hear me," implores the zarzuela "María la O," or be doomed to failed romance and perpetual bondage. In the name of the zarzuela itself, "María la O[tra]," Maria the O[ther], Lecuona lays bare the Caribbean as the resting place for the Atlantic slave trade's original sin: slavery.

Can you hear Lecuona's historical invocations in Ana María Martínez's brilliant interpretation of "María la O"?

Soundscape 2. Fernando Varela, "En mi viejo San Juan" and "Preciosa" (2017 performance)

Introduction. On Being Brown in the Democratic Commons

Soundscape 3. The Ring, "Savage Lover" (1979 and 1980)

By the time Sonia Sotomayor graduated from Yale Law and joined the Manhattan District Attorney's office in 1979 NYC was experiencing an epic crime wave. The infamous Studio 54 was spinning some of the era's most iconic underground synthesizer hits of the year and "Savage Lover" by The Ring coincided with what became known as the "Tarzan" murders and robberies in NYC that Sotomayor helped to solve as prosecutor. During her years working as assistant district attorney and trial lawyer she prosecuted offenders for robbery, assault, murder, child pornography, and police brutality.

Soundscape 4. Cerrone, "Supernature" (1977)

The French composer and record producer Ceronne had two hits that enveloped NYC record stores and soundscapes in 1979. If Sotomayor ventured into West Village, the ambient soundscape would no doubt have included Cerrone's "Supernature" which had already hit big in England as early as 1977, but settled stateside in late 1978. Along with Ceronne's "Love in C Minor" (1976), both were a fixture of downtown NYC life everywhere you went. While it is hard to imagine from our vantage point, in the absence of privatized soundscapes first introduced by SONY with the Walkman in 1979, someone else's musical tastes always wound up in your sensorium if they possessed the bass and the speaker strength to pump out the sound.

Soundscape 5. ESG, "Moody" (1981)

Like Sonia Sotomayor, the group ESG (short for Emerald, Sapphire and Gold) came of age in the South Bronx. Sisters Renne, Valerie, and Marie Scroggins created a Brown alternative to the music of the era through sheer will because they lacked the resources to buy traditional musical instruments. Instead they used borrowed synthesizers, bass and sheer talent to forge Latinx audiotopias. They're "Moody" is a syntho-disco alternative to the overproduced disco music of the day and was a fixture at the Paradise Garage, itself an epic Black and Brown queer house-music space in NYC that was demolished in 2018. It was in "Paradise," as we called it then, that as an under-age kid with a fake ID I first heard ESG. ESG was "intersectional" before we knew what the term was. They crossed genres as diverse as hip-hop, new-wave, disco, and punk. In the process, they united a truly diverse following that included homies, punksters, audacious divas, and closeted Brown queer boys like me from the NYC suburbs. Dancing to "Moody" felt as close to paradise as I could have imagined it then when ESG's pulsing bass beats reverberated through my body with what felt like freedom. We should never underestimate our petit freedoms. No matter how small, these petit freedoms allow us to inhabit imaginary elsewhere that taste like liberation. And it is in that yearning that we find the will, against escape but toward freedom, to break free from our real or imagined dispossession.

Soundscape 5. John "Jellybean" Benítez, remix of Babe Ruth's "The Mexican" (1984)

During Ronald Reagan's two-term presidency (1981-1989) public education subsidies were slashed and the neoliberal order enshrined austerity for everyone but the wealthiest as corporate taxation exemptions rose in measure with deregulation. The emergence of the "one-per-center" billionaires ballooned as waged labor stagnated under a minimum wage of $3.35 that was supported by the president.

Puerto Rican John "Jellybean" Benítez's remix of "The Mexican" reinterpreted Latinx and Black resistance to stagnant labor, and rising higher educational inequities just as the 1984 reelection campaign for Reagan kicked into high gear. John Wayne, Reagan's favorite movie-star and alter-ego, had stared in the film western The Almo (1960) which distorted the history of U.S. and Texan occupation of Mexico prior to the U.S. Mexico War of 1846-48.

The remix became a house and clubhouse anthem of resistance for urban youth who were introduced to a sonic hero, Chico Fernández, who refused U.S. imperial expansion. The remix of "The Mexican" was a circuit venue hit while Benítez was a DJ at NYC's Funhouse, the Roseland Ballroom, Studio 54 and popularized on NYC dance radio station WKTU which reached into Long Island and southern Connecticut. "The Mexican" was also a staple that year at NYC clubs and Fire Island, NY, where Sonia Sotomayor vacationed as told in her memoir, My Beloved World (2013, Chapter 24, pgs. 226-27).

Link to complete list of soundscapes: Soundscapes 6-21